Art as Political Power in the French Revolution

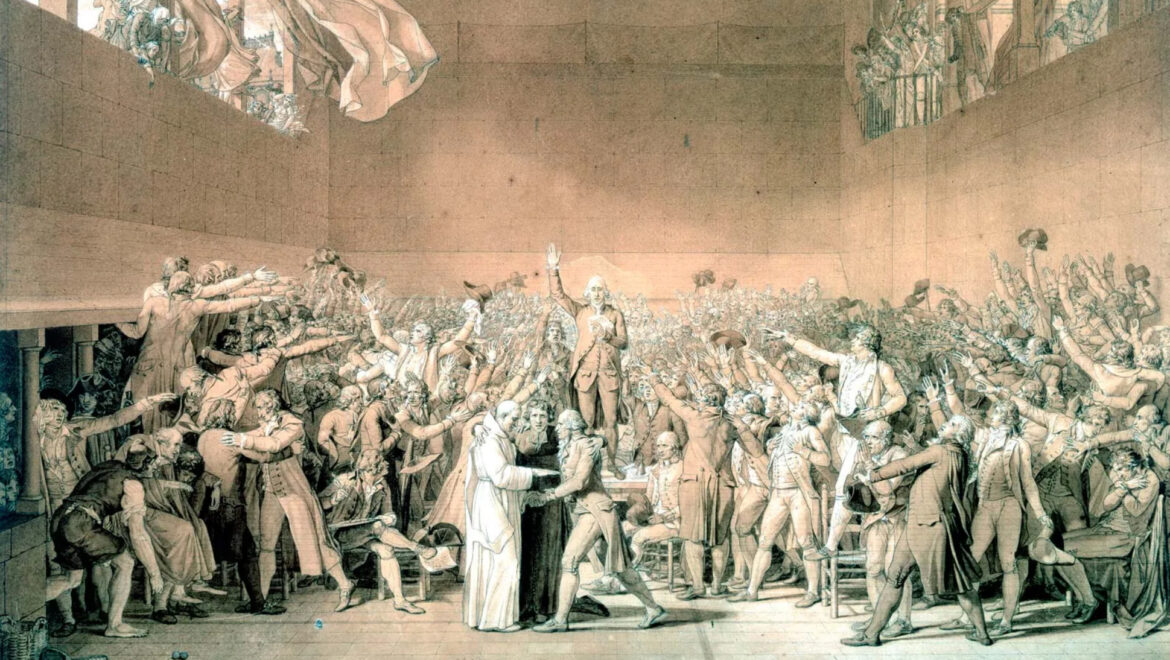

In the years surrounding the French Revolution, painting took on a new and urgent role in public life. As political systems shifted and traditional hierarchies collapsed, artists created visual masterpieces capable of expressing the ideals and tensions of the revolutionary era. The exhibition Revolution Embodied brings together a collection of paintings that demonstrate how art was not merely a reflection of political events but an active force in shaping revolutionary meaning and memory. These works reveal how artists used paint to explore concepts of sacrifice, collective identity, civic virtue, and the emotional costs of radical change. Far from passive observers, these painters participated in the construction of a new political culture. In many cases, their paintings also functioned as a form of visual propaganda, designed to influence public opinion, promote revolutionary ideals, and strengthen support for the Republic (Wilson, 2023).

In the late 18th century, France underwent dramatic political upheaval. The established ideals of a monarchy, divine rule, and religious order no longer served the rapidly evolving society. Artists responded by using imagery, emotional intensity, and powerful symbols to convey the core values of the Revolution. Among the most politically engaged of these artists was Jacques-Louis David. A committed supporter of the Jacobins, David was deeply involved in revolutionary politics and served as a member of the National Convention. He was also a close friend of Jean-Paul Marat, the radical journalist and politician whose death he would immortalize in The Death of Marat (1793). Rather than depicting the violence of Marat’s assassination, David paints an almost tranquil scene, transforming the radical figure into a martyr of the Republic. The composition is reminiscent of religious iconography, giving Marat the status of a secular saint. This painting became an emotional and symbolic touchstone for the Revolution, encouraging loyalty to the Jacobin cause and framing political sacrifice as noble and necessary. Scientific analysis of the work confirms David’s intentional construction of the image, such as his use of classical references and pigment choices to craft an idealized narrative, reinforcing Marat’s martyrdom (Defeyt et al., 2023). It was widely circulated and served as a powerful piece of revolutionary propaganda, intended to inspire continued support for the cause.

David’s political convictions were not momentary. Before the Revolution, he had already begun to engage with themes of sacrifice and civic duty, as seen in The Oath of the Horatii (1784). This painting illustrates three Roman brothers pledging to fight for their city with unwavering resolve. The dramatic gestures and solemn expressions promote the idea that duty to the state must come before personal feeling, as the women in the background grieve the likely loss of their loved ones. Though created under royal patronage, the work reflected Enlightenment ideals and later became a visual rallying point for revolutionaries. Its moral clarity and idealized figures offered a model for how citizens should serve the Republic, shaping the way viewers understood their obligations in a time of crisis. As political tensions intensified, the painting was reinterpreted as a visual endorsement of loyalty to the state, even at great personal cost (Goudie, 2015).

The impact of revolutionary painting extended beyond the 1790s. Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830), painted decades later, draws directly on the visual and symbolic strategies developed during the Revolution. Though Delacroix was not a revolutionary in the strict political sense, he was deeply influenced by Romantic ideals and supported liberal causes. His painting presents Liberty as a robust and determined figure leading citizens of all classes over the bodies of the fallen. The allegorical figure carries the French flag, and her bare chest evokes both classical imagery and maternal strength. This image became a lasting emblem of revolution, one that bridges the gap between historical event and symbolic memory. Delacroix’s artistic choices reflect his belief in the emotional power of art to engage the public and stir national sentiment. While not created as propaganda in the same way David’s works were, it nonetheless functions as inspiration and commentary, reminding viewers that the fight for freedom remains ongoing and collective.

By focusing on key works that express themes of martyrdom, civic duty, and symbolic leadership, the exhibition demonstrates that revolutionary painting played a vital role in shaping political thought and collective identity. These pieces were meticulously created in order to reinforce revolutionary ideals and solidify public support. Artists like David and Delacroix used composition, symbolism, and emotion to translate abstract ideas into compelling visual forms. Their works made liberty, justice, and sacrifice feel immediate and real to their viewers. Rather than serving as decoration or mere illustration, these paintings gave the Revolution a shared set of images through which people could interpret, embrace, or challenge the events unfolding around them.

Taken together, these works offer a focused view of how art helped define the Revolution’s emotional and ideological landscape. From the solemn dignity of Marat to the fierce resolve of the Horatii, to the enduring symbol of Liberty herself, each painting contributes to a larger visual narrative that reveals the stakes, hopes, and contradictions of a society in transformation. The enduring power of these paintings lies in their ability to move viewers, provoke thought, stir emotion, and inspire action. Through their powerful imagery and bold themes, they offer us a lasting record of how art and politics can converge to reshape a nation and redefine what it means to be free.

The continued relevance of these paintings lies in their ability to remind us that political ideas are not abstract or distant when visualized with such power. In moments of collective unrest and social transformation, imagery becomes a unifying language that transcends class, literacy, and even geography. These revolutionary works contributed to the emotional and symbolic unity that fueled lasting change. As viewers today engage with these pieces, they not only witness the past, but participate in an ongoing dialogue about justice, identity, and the enduring power of images to mobilize people and make history.